Although a species rarely encountered by Australian pest managers, the West Indian drywood termite is an invasive species that pest managers should be well informed about.

Latest drywood termite research

Ageing drywood termite frass

Whenever termite damage is detected, a common question is, “How old is the termite damage?” When it comes to drywood termites, the presence of frass (pictured above) is the key indicator of activity and therefore damage. But knowing whether frass is fresh or old is important, especially if the frass is spotted after a treatment. Is the frass fresh, indicating active termites are still present or maybe a new infestation, or is it simply old frass that has fallen out of the wood? With significant costs associated with drywood termite control measures, homeowners do not want to pay for any unnecessary treatments. Therefore, a reliable method for ageing frass would be a useful tool.

Researchers investigated colour change and difference in chemical composition as two potential methodologies to age frass.1 Colour change proved to be an unreliable methodology; although the frass does indeed darken as it ages, it cannot be used to accurately determine the age of the frass, as the initial colour can vary significantly. However, the researchers found that differences in the chemical composition have potential to age frass. Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, they could accurately differentiate frass that was less than six months old from frass that was older than 12 months. With the cost of an unnecessary drywood termite treatment being significant, the researchers concluded that this methodology was worthy of further refinement.

The use of heat to control drywood termites

Although heat treatment has been used to eliminate drywood termites from structures in the US, it is not used in Australia. Although it is considered a safer option than fumigation from a health risk and environmental point of view, the need to heat the whole structure to a high temperature for an extended period increases the potential for heat damage to decorations and belongings. In addition, due to the challenges of getting the internal temperature of wood to a lethal temperature, results are mixed. However, for spot treatments, the use of heat can prove more reliable, although there are still some significant questions around heat transfer – how long and to what temperature do you need to heat the wood to eliminate drywood termites?

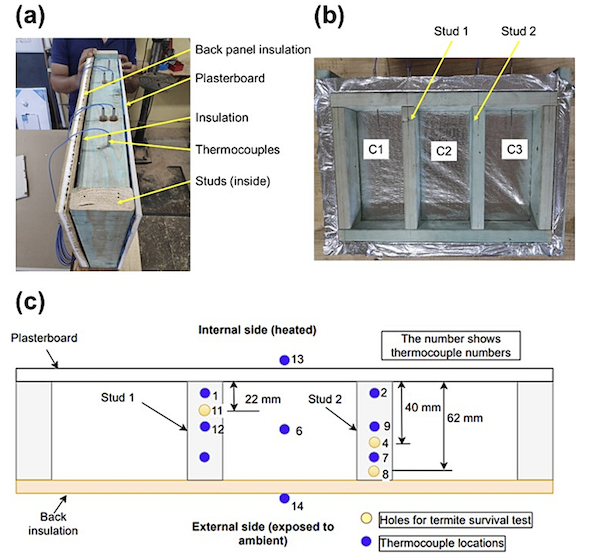

Australian researchers have developed a model to accurately predict the required heating time required to reach a lethal temperature to achieve C. brevis eradication.2 Although the ISPM 15 (International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures 15: Regulation of Wood Packaging

Material in International Trade) specifies raising the internal temperature to a minimum of 56ºC for 30 minutes, the researchers found alternative heating/duration regimes proved efficacious. Evaluating different heating regimes and assessing drywood termite mortality at different depths in the wood from the heated surface, they determined that as long as the internal temperature was above 45ºC for at least three hours, 100% mortality could be achieved within 24 hours.

To achieve this, a heat of 60ºC was applied at the surface. The time taken to reach the required temperature depends on a variety of factors including wood species, density and moisture content. However, the researchers concluded that heating could be used as a cost-effective control method for spot treatments in structural elements.

Natural attractants to boost performance of drywood termite treatments

Spot insecticide treatments for drywood termites have their challenges, primarily in ensuring enough of the termites get a dose of the insecticide. The use of attractants to lure termites to insecticide-treated zones has been proposed as a technique to boost performance. Researchers in the US have evaluated pinenes, which are found in many coniferous trees, for their potential as drywood termite attractants.3

Using Incisitermes minor, the western drywood termite, the researchers carried out a number of laboratory studies using artificial galleries in Douglas fir wood blocks. The studies demonstrated that both á-pinene and ß-pinene were attractive to the worker termites, increasing the likelihood that they would move away from their original aggregation site. However, ß-pinene appeared to be the more attractive of the two isomers. Indeed, when added to a fipronil treatment, the termites were killed more quickly and the final mortality level was higher than the fipronil-only treatment. Further research is required to confirm performance and also evaluate whether the use of such attractants could reduce the number of drill holes and/or reduce the amount of insecticide used in treatments.

The potential for using chitin synthesis inhibitors for drywood termite control

Spot treatment using an insecticide is an accepted control method for small drywood termite infestations. The success of such treatments requires accurate application to the infested area and for the insecticide to be non-repellent, slow acting and transferable. Although fipronil, thiamethoxam and borate are used in treatments, results can be variable often due to incomplete coverage caused by application limitations and the complicated nature of the termite galleries. Laboratory studies have shown that when only a limited number of termites received a direct dose of these insecticides, the level of transfer from these donor termites to recipient termites appears limited, resulting in incomplete control. Researchers in the US carried out a series of studies to see whether chitin synthesis inhibitors (CSIs) may be a better option.4

CSIs certainly have the three essential characteristics for a potential drywood termiticide. The researchers evaluated the performance of three CSIs: bistrifluron, chlorfluazuron and noviflumuron. When applied to pieces of wood, bistrifluron delivered faster and more complete mortality than both chorfluazuron and noviflumuron, in both choice (termites could choose between treated and untreated wood) and no-choice bioassays. At the 60-day mark, bistrifluron had delivered 99% (no-choice trial) and 96% (choice trial) mortality.

Taking bistrifluron forward to transfer studies, 88% mortality was achieved with a 10:10 donor recipient ratio and 81.5% mortality was achieved with a 1:19 donor recipient ratio. The researchers concluded that bistrifluron has the potential for use as a direct insecticide treatment for drywood termites, although work on formulation development for optimal in-field application would be required as part of future studies. In addition, it suggests that bistrifluron has potential for use in an injectable drywood termite baiting system.

Orphaned drywood termite colonies produce replacement reproductives

“Kill the queen and you kill the colony” is a popular mantra when it comes to controlling colonial social insects. However, termites have fairly plastic developmental pathways, which can allow them flexibility in the development of reproductives and conveys robustness in dealing with adversity. Researchers have demonstrated that five-year-old colonies of the drywood termite Cryptotermes domesticus can survive the death of the reproductive pair.5 After removal of the original primary reproductive pair, all 15 experimental colonies in the study survived and were successfully re-established with a neotenic reproductive pair. On average, it took just over 100 days for the new reproductive pair to develop from nymphs and take over reproduction in the colony.

References

1 Haigh, W. et al. (2024) ‘Use of Chemical and Colorimetric Changes to Age Cryptotermes brevis Frass for Termite Management’, Insects, 15(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/insects15120924

2 Kumar, C., Hassan, B. and Fitzgerald, C. (2024) ‘Investigation of heat transfer in timber boards and a simulated wall section to eliminate colonies of the west Indian drywood termite, Cryptotermes brevis (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae)’, Austral Entomology, 63(4), pp. 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/aen.12708

3 Poulos, N.A. et al. (2024) ‘Potential use of pinenes to improve localized insecticide injections targeting the western drywood termite (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae)’, Journal of Economic Entomology, 117(4, SI), pp. 1628–1635. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toae101

4 Poulos, N.A. et al. (2025) ‘Toxicity and horizontal transfer of chitin synthesis inhibitors in the western drywood termite (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae)’, Journal of Economic Entomology. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaf064

5 Wu, W. et al. (2024) ‘Types and Fecundity of Neotenic Reproductives Produced in 5-Year-Old Orphaned Colonies of the Drywood Termite, Cryptotermes domesticus (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae)’, Diversity-Basel, 16(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/d16040250

The economic impact of banning sulfuryl fluoride for drywood termite treatments

Due to its potential role in global warming, there is increasing regulatory pressure to ban the use of sulfuryl fluoride as a fumigant for drywood termite control. As sulfuryl fluoride is the sole remaining fumigant available for the treatment of several structural pests, including drywood termites, researchers have developed an economic framework to assess the impact of banning sulfuryl fluoride to help inform decision makers.1

Looking at the drywood termite market in California alone, the researchers estimated that the transition from a combination of fumigation (whole of house) and local (spot) treatments, which is the makeup of the current market, to a market entirely based on local treatments, would see costs to the public increase by a low estimate of US$1.42 billion (due to increased treatment cost and increased damage) to a high estimate of US$4.31 billion. This effectively puts a cost per ton of carbon dioxide at US$624-1475, should sulfuryl fluoride by banned. This is significantly higher than the price range for carbon dioxide calculated for other industrial applications, which is typically in the range of US$30-150 per ton. As a result, the authors see the banning of sulfuryl fluoride as a suboptimal option, at least until a suitable alternative can be identified. But as the authors also point out, research and innovation to find a suitable alternative are lacking.

Spot treatment alternatives for drywood termites

In Australia, fumigation for drywood termites is very expensive, yet local (spot) treatments are not without their issues. Apart from the challenge of ensuring all infested areas in the structure are treated, even treating a single area of infestation can be challenging as it can be difficult to get the treatment to penetrate all the galleries in the wood.

Foams are commonly used to carry out localised treatments for subterranean termites. Researchers in the Queensland Government evaluated two non-repellent actives commonly used in subterranean termite treatments, fipronil and imidacloprid, for their performance on drywood termites in a foam format.2 In summary, whilst both insecticides delivered 100% control when applied topically or as a residue in continuous exposure, imidacloprid did not deliver 100% mortality when the drywood termites were exposed to residues for a short period and indeed, the speed of kill was slower for imidacloprid than fipronil in all trials.

Interestingly, the imidacloprid foam showed high levels of repellency as a residual treatment – up to 90% after 24 hours, whereas the fipronil foam was only slightly repellent when fresh, but non-repellent after 24 hours. These properties resulted in corresponding levels of mortality – low levels with imidacloprid and high levels with fipronil.

Additional trials were carried out with the fipronil foam to assess horizontal transfer. The results demonstrated that fipronil was passed from donor termites to recipient termites. At a 1:1 ratio, 100% mortality of the recipients occurred after approximately two weeks. However, at a ratio of 1 donor to 9 recipients, the mortality rate was slower, and 100% mortality was not achieved even after the 26 days of the study. This is in line with studies on subterranean termites that emphasise the importance of getting the insecticide to as many termites as possible to maximise the donor:recipient ratio and therefore horizontal transfer.

The authors state the need for field trials to confirm performance, with particular concern that for liquids and foams, frass in the galleries may prevent movement of the treatment within the galleries.

As a result of these findings, the same authors investigated the possibility of using synergised pyrethrum in an aerosol format to treat drywood termites.3 The laboratory study demonstrated that synergised pyrethrum delivered very rapid mortality of drywood termites when exposed to treated surfaces. Interestingly, the residual performance was seen to continue for at least two months. Importantly, the aerosol formulation penetrated loose frass barriers, which would allow for more complete treatment in the field. The researchers noted the need to carry out field trials to determine its effectiveness in the field.

References

1 Zilberman, D. and Lewis, V.R. (2024). Economic framework to assess the impact of banning pesticides, with application to sulfuryl fluoride for drywood termites (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae) in California. Journal of Economic Entomology. 117(1): 1-7, https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toad200

2 Hassan, B et al. (2023). Toxicity, repellency, and horizontal transfer of foam insecticides for remedial control of an invasive drywood termite, Cryptotermes brevis (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae). BioResources 18(2):2589-2610.

3 Hassan, B and Fitzgerald, F. (2023). Potential of Gas-Propelled Aerosol Containing Synergized Pyrethrins for Localized Treatment of

Cryptotermes brevis (Kalotermitidae: Blattodea). Insects, 14(6): 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14060522

About drywood termites

The West Indian drywood termite, Cryptotermes brevis, is one of the most difficult termites to control and an important invasive termite, with its distinctive pellet-like frass (pictured) helping in its identification. Due to its nesting behaviour, where it develops small nests completely within its wood food source that can survive at low moisture levels, the nests are difficult to detect and easy to inadvertently transport.

When buildings become infested, control is difficult as the standard treatment is to fumigate the entire building, which tends to be expensive and concerning from a safety and environmental point of view. This issue is of particular focus in Australia at the moment, as although the West Indian drywood termite is classified as an invasive pest, the Queensland Government has decided that when an infestation is identified, the cost of the treatment is now the responsibility of the property owner.

Drywood termite control — the heat is on!

With heat treatments being utilised commercially for other pests, the question is whether this is a suitable technique for the control of drywood termites. The challenge in using heat treatment for drywood termites is that whereas treatment of wooden furniture may be possible, treatment of whole buildings becomes more problematic.

Australian researchers have established that although exposure to 40°C for up to an hour did not kill the termites, exposure at 45°C for one hour was lethal.1 Higher temperatures were even more effective — as little as three minutes’ exposure at 50°C or two minutes at 55°C was lethal. The researchers suggested that localised heat spot treatment could be an effective option. However, getting the internal temperature of the wood (where the termites are hiding) up to the required heat level can be a challenge.

However, in the US, heat treatment is increasing in popularity to treat West Indian drywood termite infestations, although they suffer from the same issue, that such treatments may not be able to kill all the termites due to the difficulty in heating some areas. Focusing on blocks of units, where West Indian drywood termites primarily infested wooden furniture and kitchen cabinets, researchers identified ways to improve the heat circulation in treatments.2 The key action they took was to drill holes in the base of kitchen cabinets and pump heated air into these voids. The result was a 100% success rate, rather than a 33% callback rate with standard heat treatments. The researchers emphasised the importance of achieving even heat distribution, not only to ensure control, but to avoid the need to try and heat to excessive temperatures to overcome the failings of poor heat distribution.

References

1 McDonald, Janet & Fitzgerald, Chris & Hassan, Babar & Morrell, Jeffrey. (2022). Thermal tolerance of an invasive drywood termite, Cryptotermes brevis (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae). Journal of Thermal Biology. 104. 103199. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2022.103199.

2 Tay, Jia-Wei & James, Devon. (2021). Field Demonstration of Heat Technology to Mitigate Heat Sinks for Drywood Termite (Blattodea: Kalotermitidae) Management. Insects. 12. 1090. 10.3390/insects12121090.

Further reading:

General information on termites